Bryan Stevenson has been –and continues to be – a personal role model, a hero and an inspiration, ever since the first time I heard him speak twenty-five years ago. I later had the pleasure of collaborating with him on national agenda issues when I was doing death penalty work in Texas; we endeavored to put monkey-wrenches into ‘the machinery of death‘ back when executions were not a rarity, when nobody had funding, when Alabama was awful but Texas was, in some ways, even worse.

Bryan Stevenson has been –and continues to be – a personal role model, a hero and an inspiration, ever since the first time I heard him speak twenty-five years ago. I later had the pleasure of collaborating with him on national agenda issues when I was doing death penalty work in Texas; we endeavored to put monkey-wrenches into ‘the machinery of death‘ back when executions were not a rarity, when nobody had funding, when Alabama was awful but Texas was, in some ways, even worse.

Even then, Bryan was a shining star in the close-knit death penalty defense community. None of us were the least bit surprised when the McArthur Foundation selected him for their “genius” award. But Bryan — and the others at the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) — toiled in relative obscurity for another decade or two before the rest of the world began to notice the important work they were doing. In Alabama, and across the country, Bryan serves the poor, the disenfranchised, the innocent, and has been a champion for children who were set to be executed, or serving a sentence of ‘death in prison‘ (just one of the brilliant phrases that Bryan coined – most people would call that a ‘life sentence’ but Bryan rightly pointed out that sending a 14 year old to prison for the rest of his natural life is really sentencing him to death, in prison.)

Then in 2012, Bryan was invited to speak on the TED stage. (If you haven’t watched his TED Talk, stop reading this RIGHT NOW and go watch it. Really. It is the best way to spend the next 20 minutes of your life. DO IT!) And the rest of the world learned what some of us had known for many years — Bryan Stevenson is brilliant; a man with a story, a genius worth listening to.

One of the great things about Bryan’s TED Talk is that it made the work he does accessible. When somebody tells you they represent those who have committed heinous crimes, there is a tendency to either run in the other direction, or simply stop listening. But when Bryan describes his life’s work, you cannot turn away. You recognize he is one person who has become, like Gandhi recommended, “the change you want to see in the world.”

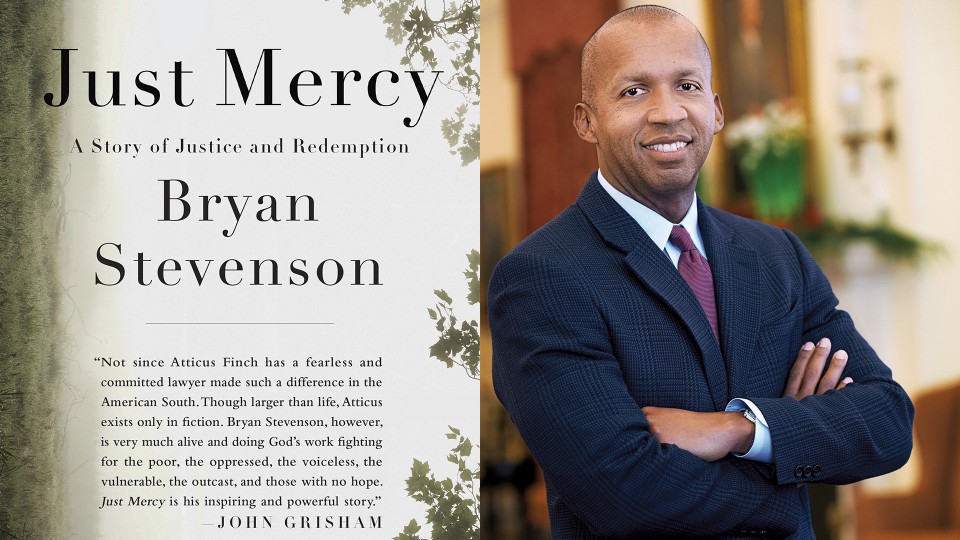

Just Mercy seems to be the logical next step to Bryan’s TED Talk. It too is accessible. It is beautifully written. It tells stories that will move you to outrage, to tears, to laughing out loud. And, ultimately, to question how one ordinary man can do so much, and why you aren’t doing more.

This is the kind of wisdom captured in its pages:

Proximity has taught me some basic and humbling truths, including this vital lesson: Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done. My work with the poor and the incarcerated has persuaded me that the opposite of poverty is not wealth; the opposite of poverty is justice. Finally, I’ve come to believe that the true measure of our commitment to justice, the character of our society, our commitment to the rule of law, fairness, and equality cannot be measured by how we treat the rich, the powerful, the privileged, and the respected among us. The true measure of our character is how we treat the poor, the disfavored, the accused, the incarcerated, and the condemned. (p. 17)

Those powerful words capture the soul of this book. They are the lessons that Bryan, through Just Mercy, teaches. As importantly, the pages of this book lay out the essence of social justice in our time.

Since writing Just Mercy, Bryan and EJI have expanded the work they do to promote social justice. In April 2018, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened in Montgomery, Alabama. It is “the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence.” Next to the Memorial is the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration. The museum “is situated on a site in Montgomery where enslaved people were once warehoused. A block from one of the most prominent slave auction spaces in America, the Legacy Museum is steps away from an Alabama dock and rail station where tens of thousands of black people were trafficked during the 19th century.” The Memorial and the Museum are extensions of the work that Bryan and EJI have done for decades — fighting on behalf of those marginalized by our systems of injustice. They now have created a tangible space designed to be “an engine for education about the legacy of racial inequality and for the truth and reconciliation that leads to real solutions to contemporary problems.” It is worth a visit.